EXECUTIONS AT TYBURN

Executions at Tyburn

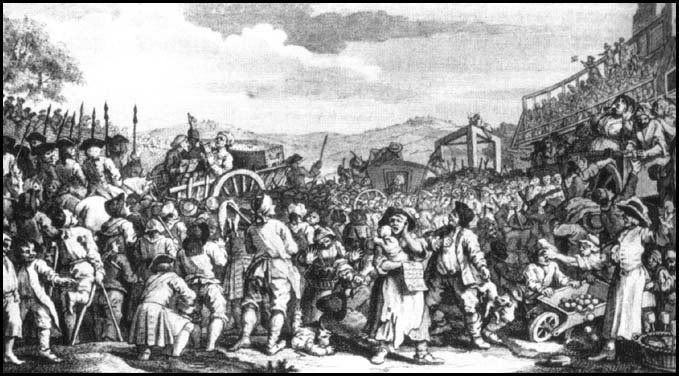

Executions at the permanent gallows at Tyburn , west of the city, were an enormously popular tourist attraction and created an instant celebrity of the condemned. William Hogarth's depiction of the Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn,( ABOVE ) part of a series called Industry and Idleness. In the right background can be seen the triple tree of Tyburn; each of its three horizontal beams could hang eight men at once. The hangman is seen casually smoking his pipe on one of these beams. The condemned is arriving in a cart, left midground, accompanied by his coffin and an exhortative preacher. In the foreground a poor woman, holding her baby, is selling what purports to be the condemned's dying speech.

Newgate Prison

For a gaoler's fee, the public could view the condemned the day before an execution and even be let into his cell at Newgate Prison. The Fatal Bellman

In 1605, a wealthy merchant and tailor named Robert Dow bequethed 50 pounds to have a bell rung outside the cell of the condemned at midnight before an execution. The Bellman of St. Sepulchre (a clerk at the church) would recite the following while ringing a handbell: All you that in the condemned hole do lie,

Prepare you for tomorrow you shall die;

Watch all and pray: the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear;

Examine well yourselves in time repent,

That you may not to eternal flames be sent.

And when St. Sepulchre's Bell in the morning tolls

The Lord above have mercy on your soul.

Prepare you for tomorrow you shall die;

Watch all and pray: the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear;

Examine well yourselves in time repent,

That you may not to eternal flames be sent.

And when St. Sepulchre's Bell in the morning tolls

The Lord above have mercy on your soul.

The Procession

Early the following morning, the prisoner would be moved from Newgate Prison on a cart, often seated on his own coffin, with a prison chaplain. When the procession reached the steps of St. Sepulchre, the criminal would be given brightly colored nosegays by friends, the church bell would sound, and the clerk would chant, "You that are condemned to die, repent with lamentable tears; ask mercy of the Lord for the salvation of your souls." As the parade passed by, the clerk would tell the audience, "All good people, pray heartily unto God for these poor sinners who are now going to their death, for whom the great bell tolls." According to the popularity of the criminal, he could be pelted with rocks and other missiles or cheered along the two-hour trip to Tyburn. Last Words

After drinking with the hangman at a tavern along the way and saying prayers with the chaplain, the condemned would arrive at the gallows with the expectation of a "last dying speech ," his final penitent words on the precipice of eternity. Not all prisoners were willing to follow the script due to claims of innocence, resentment of the spectacle, religious beliefs or complete inebriation. In any case, this was a high theatrical moment that many dramatists found too rich to overlook on the stage. Considering the popularity of the Tyburn spectacle and its cultural importance to Londoners, it is little wonder that Shakespeare makes a reference to hanging (literally or by the popular oath "go hang!") in almost all of his plays. Emotions could run high at executions and sympathy was often stirred up in the crowd. There are instances of riots breaking out when surgeons tried to claim dead bodies after a hanging for purposes of dissection. In 1586, when the Babington conspirators were hanged, drawn, and quartered, there was such a public outcry concerning the barbarity of the procedure that the authorities decided only to hang the next seven the following day. Obviously, there were limits to the support that could be given by the public.

Reading an Execution

Execution was an aesthetic as well as emotional experience. The ars moriendi tradition enjoyed a strong revival under Elizabeth and the Stuarts; how one died was as important as how one lived. The execution ritual was an instrument of the state but was a highly personal statement for the individual as well. The public clambered for chapbooks containing accounts of the condemned's behavior and the wisdom of their last words. The executions scene, like plays, were "read" by audiences of the time and almost always moralized. Most accounts editorialize the final performance of the condemned as successful (died well) or disgraceful (died badly). Pamphlets recording "last dying speeches " were more a literary genre than a form of journalism and were so popular that they continued until the 18th century.

No comments:

Post a Comment