About Me

- the-old-bailey

- United Kingdom

- Name: THE OLD BAILEY . Favorite quote: "Defend the Children of the Poor & Punish the Wrongdoer". Location: London. Hometown: LONDON Places lived: ALWAYS ON OLD BAILEY , LONDON. More about you: BUILT IN 1907 AND ADDED TO IN 1972 ON THE SITE OF NEWGATE PRISON. Occupation: A place of history and law. THIS WEBSITE HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH THE CITY OF LONDON OR THE MINISTRY OF JUSTICE.

Tuesday 30 November 2010

Saturday 27 November 2010

Thursday 25 November 2010

Wednesday 24 November 2010

The RATTENBURY Murder , 1935.

| Bournemouth’s most sensational murder |

| The Rattenbury murder of 1935 is recalled by John Walker ( Dorset Life - The Dorset Magazine ) |

Francis Rattenbury at the peak of his success in British Columbia

In his book, Murder at the Villa Madeira, eminent lawyer-author Sir David Napley introduces the Rattenbury murder as follows: ‘The sensation of the year 1935 was the trial at the Old Bailey on charges of murder of Alma Rattenbury, an attractive woman of perhaps 39 or 40, and her lover, George Stoner, who had been employed in her house as a chauffeur-handyman.’ It was certainly the biggest local sensation in Bournemouth that year, and the biggest ever on its East Cliff. Although the murder in question took place in March 1935, our story really begins the previous September when the following advertisement appeared in the Bournemouth Daily Echo: ‘Daily willing lad, 14-18, for house-work; Scout-trained preferred. Apply between 11-12, 8-9 at 5 Manor Road, Bournemouth.’ 5 Manor Road on Bournemouth’s East Cliff was also known as the Villa Madeira. Five people were then resident in the house. They were 67-year-old retired architect Francis Mawson Rattenbury, his 39-year-old wife of ten years, Alma, her 13-year-old son by a previous marriage, Christopher, their own 6-year-old son, John, and Alma’s live-in companion-housekeeper, Irene Riggs. In November 1934 the ‘Daily willing lad’ who had answered the advertisement two months before and become the family’s chauffeur-handyman, 18-year-old George Stoner, also became a permanent resident. Sadly, nine months later, this ‘willing lad’ would be on trial at the Old Bailey for his very life.

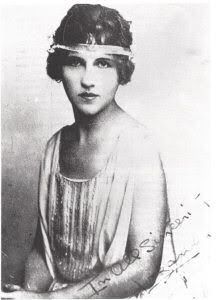

A picture of Alma as Lozanne, her musical pen-name, may give an idea of why she attracted three husbands and at least one lover .

Francis Mawson Rattenbury, Yorkshire born and bred, sailed from England to Canada in 1892 at the age of 24 to seek his fame and fortune as an architect in the developing area of British Columbia. He was not to be disappointed. Within a year he had won an open competition to design the Parliament Buildings for Victoria, the town selected as British Columbia’s capital. The resulting edifice met with widespread approval and he came to be in great demand. His later work included the Law Courts in Vancouver and the luxurious Empress Hotel on Victoria’s waterfront, a venue that would play a pivotal role in his private life. In between these successes, Francis led a roller-coaster life. Often ruthless and aggressive in dealing with others, he received little sympathy when failed private business ventures left him short of funds with only his architectural talent to fall back on. To make matters worse, on 29 December 1923, while celebrating the award of an important local contract in ‘his’ Empress Hotel, the 56-year-old Rattenbury met and fell in love with Alma Pakenham, a divorcée half his age. Once their affair became public knowledge, Rattenbury then married with two children and considered a pillar of local society, was no longer welcome in Victoria. An acrimonious divorce followed and the newly-weds, together with Alma’s son, Christopher Pakenham, finally settled in Manor Road on Bournemouth's East Cliff.

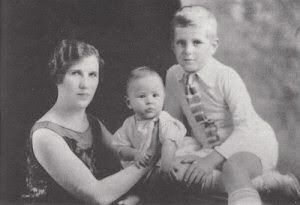

Alma with John and Christopher

Alma herself grew up in British Columbia. In her teenage years she lived in Vancouver and, with her mother’s guidance, became an accomplished musician, something she was able to fall back on in later years. At 19 she married the love of her life, Ulsterman Caledon Dolling, and followed him to England when he enlisted in the Army in World War I. On receiving the tragic news that Dolling had been killed at the Battle of the Somme, Alma immediately joined a Scottish ambulance unit that she knew would be working behind the French lines. Her bravery in this situation led to her being awarded a leading French medal, the Croix de Guerre with Star and Palm. At the end of World War I, she married Captain Compton Pakenham and moved with him to America. Following the birth of Christopher, the marriage broke up and she and her son joined her mother in Vancouver. Alma returned to music professionally and one day, after performing in Victoria, found herself enjoying a relaxing drink at the Empress Hotel with a friend; it was 29 December 1923. When she married Rattenbury in 1925 at the age of 29, the now thrice-married Alma had borne one son (Christopher), been cited as co-respondent in two divorce cases (Pakenham’s and Rattenbury’s), enjoyed fame as a musician and received a top French military honour. Quite a life so far! By contrast, the third member of our trio, 18-year-old George Stoner, was rather shy and retiring, having been rather a loner as a child with no serious girl-friends. His time had been spent between the family home in Redhill, Bournemouth and his grandparents’ house in Ensbury Park, Bournemouth. A handsome lad, the fact that he could drive and thus work as a chauffeur-handyman was a big plus to the Rattenburys when they employed him in September 1934. Two months later he was living in at the Villa Madeira and embarking on a passionate affair with Alma Rattenbury. Because of their respective backgrounds and ages, it must be assumed that Alma was very much the instigator.

George Stoner

By November 1934 Francis Rattenbury was often depressed and suicidal. Now impotent – he and Alma had not had sexual relations since the birth of John – he took refuge in a nightly bottle of whisky. He slept on his own downstairs and appears not to have objected to his wife’s affair; in such a small house it is almost inconceivable that he did not know what was going on. For her part, Alma, still attractive and hoping to enhance her blossoming career as a songwriter, was caught in a dreary domestic situation. The affair continued for a few months, with Stoner visiting Alma’s bedroom at night. As time went on, however, the formerly shy Stoner, quite unnecessarily, became increasingly aggressive and possessive of Alma, expressing jealousy whenever she and Francis spent time together. Matters came to a head over the weekend of 23/24 March 1935, just after Alma and Stoner returned from a trip to London. Francis was particularly depressed and to cheer him up, Alma organised for them to visit a friend in Bridport the following week. On the afternoon of 24 March, Stoner had borrowed a wooden mallet from his grandparents in Ensbury Park, supposedly to erect a screen in the garden. Later that evening, Francis was found seriously injured, bludgeoned with a weapon that turned out to be the same mallet. It was not until doctors had taken Francis to hospital for examination and wiped the matted blood away from his head that they realised foul play had taken place and informed the police.

Alma and Francis in happier days

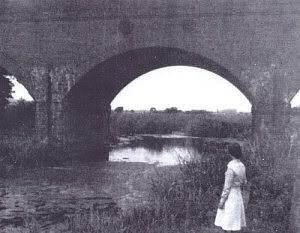

It was therefore the early hours of Monday morning before the police arrived at the Villa Madeira, by which time Alma was very much the worse for wear through drink or drugs and kept repeating that she had ‘done him in’. She repeated that same story the following morning and was arrested for attempted murder, Francis being still alive at this time. Two days later, Stoner confessed to companion-housekeeper Irene Riggs that he had done the deed and he was also arrested. On the Thursday, Francis Rattenbury died of his injuries and the charges became ones of murder. Alma Rattenbury and George Stoner were tried together at the Old Bailey on 27 May 1935, there being far too much local interest for the case to be heard at Winchester. By this time both defendants had been persuaded to plead not guilty. Stoner refused to say anything at the trial other than answer to his name, while Alma put up a robust defence. Four days later, Stoner was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death and Alma was released. It does seem likely that he was the only one involved. A possible explanation is that in a jealous rage, he had only intended to harm Francis enough to stop the proposed visit to Bridport rather than to murder him. Public sympathy was with the convicted Stoner, led astray by a much older woman, and a haggard-looking Alma was booed by a large crowd as she left the Old Bailey. A few days later, she took the train from Waterloo to Christchurch and walked across the meadows to Three Arches railway bridge, which spans a tributary of the River Avon. After writing some notes on the bankside, she walked towards the water and, plunging a knife several times into her heart, died almost immediately. It is clear from the notes and from the words of a song she wrote while awaiting trial – subsequently published as ‘Mrs Rattenbury's Prison Song’ – that she really did love Stoner, who she thought was soon to be hanged. She had died of shame. Stoner, when informed of her death, broke down and cried. At Alma’s funeral and burial at Bournemouth’s Wimborne Road Cemetery, a few yards from where her late husband lay, signatures were already being collected for mercy for the ‘led astray’ Stoner. A petition containing an amazing 320,000 signatures, including those of the local Mayor and MP, was later handed in to the Home Secretary, who commuted Stoner’s sentence to penal servitude for life. A model prisoner, he was released seven years later in 1942, then joined the Army for the remainder of World War 2. He returned to live the rest of his life in the house in Redhill he had left at the age of 18. He died in Christchurch Hospital in 2000 aged 83, not much more that half a mile from where Alma perished and on exactly the 65th anniversary of Francis’s murder! Despite all this drama, the two boys innocently caught up in the case both went on to lead happy family lives and have successful professional careers. The only person still alive today from the whole sorry saga is John Rattenbury, now 77 and a successful architect (like his father) in America.

Three Arches, where Alma committed suicide

The CUMMINS Trial , 1942

Gordon Frederick Cummins

Cummins was a 28-year-old sexual psychopath who killed four women in six days and was executed on 25 June 1942. He was good looking, well-educated and came from a good family. He was born in New Earswick, north of York. He was called to the colours in 1941 and joined the RAF. He was nicknamed 'The Count' and 'The Duke' by his fellow airmen because of his social pretensions.

On Saturday 8th February 1942 he visited his wife, borrowed some money and went into the West End of London for a night on the town. Early the next morning the body of 40-year-old Miss Evelyn Hamilton was found in an air-raid shelter near Marble Arch. The motive appeared to be theft as Miss Hamilton's handbag containing £80 was missing. Her clothing had been disarranged but she had not been sexually assaulted. Police quickly determined that her killer was left-handed.

That night, Sunday 9th, he accompanied a 35-year-old prostitute, Mrs Evelyn Oatley, back to her home. Her strangled, almost naked body was found the next day. Her body had been mutilated with a can-opener and her throat had been cut after she had been strangled.

On Thursday 13th February another prostitute, 43-year-old Mrs Margaret Lowe, was slaughtered in her Gosfield Street flat. She had been strangled with a silk stocking and slashed, this time a knife and a razor causing the damage. While the scene was being initially examined news came in of yet another victim. This was 32-year-old Mrs Doris Jouannet. Her body was found in the two-roomed flat she shared with her elderly husband. Again, the naked body had been savagely mutilated.

The following day Mrs Greta Heywood was picked up by Cummins. She went for a drink with him but refused his advances to her on their way home. She hurried off into the blackout but he chased after her. He caught up with her in St. Alban's Street, forcing her into a shop doorway where he seized her by the throat. She collapsed unconscious but a delivery-boy who happened to be passing decided to investigate the sounds of a struggle. Cummins ran off into the darkness. Unfortunately for him he left behind his gas-mask which bore his serial number, rank and name.

Not to be deterred, he shortly picked up another prostitute, Mrs Mulcahy, in Regent Street. He gave her £5 while they went by taxi to her flat in Paddington. When they got there she started to remove her clothes. According to Mrs Mulcahy, 'a strange look came over his face.' Cummins grabbed her by the throat and squeezed. Mrs M, who had kept her boots on because of the cold, kicked him in the shins, making him release her. Cummins recovered his composure, gave her another £5, and left. He left his belt behind this time.

When police traced Cummins he had a seemingly perfect alibi. His name was in the booking-out book as having returned before midnight all week. This was earlier than the times when Evelyn Oatley, Margaret Lowe and Doris Jouannet had all been killed. DCI Greeno, investigating the case, quickly established that it was standard practise for airmen to sign each other in and that one night Cummins had left with another airman, by way of a fire escape, after checking in. Cummins was searched and a cigarette case belonging to Mrs Lowe was found in his tunic pocket. He had also taken a fountain pen belonging to Mrs Jouannet and his fingerprints matched those found on the tin-opener in Evelyn Oatley's flat.

His trial began at the Old Bailey on 27 April 1942. It finished the next day and the jury took just 35 minutes to find him guilty. He was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 25 June 1942, still proclaiming his innocence.

Neville Heath

Neville Heath

It was at the Pembridge Court Hotel in May 1946, just after the War, where a 32 year old woman Margery Gardner went to a hotel room with a good-looking younger man, the so-called Lt Colonel Neville Heath. They settled in to a night of adventure in the hotel room, but an alert member of the hotel staff interrupted proceedings, and, in retrospect, probably saved Margery Gardner's life.

Margery Gardner

But Margery Gardner was a risk taker and agreed to accompany Heath back to his room in the same hotel on 20th June. Heath opened the hotel door with his key - there was no night porter - and he took her up to Room 4. The next morning the chambermaid found the room in disarray, and the dead body of Margery Gardener, horribly mutilated. There was no sign of Heath, who by this time had gone down to visit his unofficial fiancee - a Miss Symonds - in Worthing. From there he went to Bournemouth - with a new name and rank of Group Captain Rupert Brooke.

On 3rd July he entertained Miss Doreen Marshall to dinner at the West Cliff hotel, Bournemouth, and escorted her out of the premises at about 11.30pm. Doreen Marshall was never seen alive again. The so-called Rupert Brooke was called on to help the Bournemouth police to investigate her disappearance, and the local police officer, Detective Constable Souter, recognised his similarity to pictures of Heath issued by Scotland Yard and challenged him. Heath denied it, but he was kept at the station until Detective Inspector George Gates arrived.

Doreen Marshall

The police found a railway ticket belonging to Doreen Marshall, a pearl from her necklace, and a left luggage ticket. George Gates reclaimed Heath's left luggage, opened his suitcase and found articles with the name Heath on. He also found blood-stained clothing which had hairs which came from Margery Gardner and a blood-stained riding switch.

Detective Inspector Reg Spooner from Scotland Yard arrived and took him back to London, at about the same time as Doreen Marshall's body was found, again brutally and sadistically murdered.

Heath went for trial at the Old Bailey and because of the forensic science evidence against him, the only issue was whether he was mad or not. He was found sane, and Guilty. When he was about to be hanged he is said to have asked the hangman Albert Pierrepoint for a whisky, and then added "I think I'll make it a double"

Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen

Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen

FROM : stephen-stratford.co.uk

Introduction

The case of Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen is one of the most famous British criminal cases. This was the first major case that Bernard Spilsbury, the famous pathologist, was called in to investigate. The case also involved the major use of radio in tracking down the suspects.

The Case Details

Crippen in the USA

Hawley Harvey Crippen was born in Michigan, USA, in 1862. When he was 21 he came to England to improve his medical knowledge. He obtained a diploma, which was endorsed by the Faculty of the Medical College of Philadelphia, and in 1885 Crippen acquired another diploma, as an eye and ear specialist, from the Ophthalmic Hospital in New York. These qualifications were not sufficient for Crippen to practice as a Doctor in the UK.

After Crippen's first visit to England he wandered about the USA, practising in a number of larger cities. In Utah, during 1890 or 1891, his wife died, and he sent is 3 year old son to live with her late wife's Mother in California. During one of his stays in New York he married again. His second wife was a girl of 17 years old whom Crippen knew as Cora Turner. Her real name was Kunigunde Mackamotski, her Father being a Russian Pole and her Mother German. There were more wanderings: St. Louis, New York and Philadelphia, with a short visit across the border to Toronto. The Munyon Company, a patent medicine company, now employed Crippen. Mrs. Crippen, who was deluded by her modest singing talent, travelled to New York for opera training.

Crippen arrives in the UK

In 1900 Crippen was in England again, and except for one short interval, remained in England. He became the manager at Munyon's offices in London's Shaftesbury Avenue, and later in the year his wife joined him in rooms in South Crescent, off Tottenham Court Road, At one period, it is said, that he practising as a dentist and a women's consultant. In 1902 Munyon's recalled him for six months in Philadelphia. Mrs. Crippen had been seeking music-hall work, with slight success. During one of her music engagements, she met an American music-hall performer called Bruce Miller (who later testified at the trial).

When Crippen returned to London the Crippens lived at 34-37 Store Street, Bloomsbury. Crippen, who was small in height, left Munyon's for a variety of jobs. Some of them failed, and presently he eventually returned to Munyon's, who had relocated to Albion House, New Oxford Street. In Albion House, when Munyon's business began to decline, Crippen was also in partnership with another firm: The Yale Tooth Specialists. While working here, Crippen employed as his typist Ethel le Neve. He had first met her when they had been working for one of Crippen's business failures: The Drouet Institute. Although Crippen took over the Munyon's office on a franchise basis, he failed to halt Munyon's decline and Crippen ended his 16 year relationship with the Munyon firm on 31 January 1910.

The move to 39 Hilldrop Crescent

MRS. CORA CRIPPEN

During this period, the Crippens moved into a house in Camden Town: number 39 Hilldrop Crescent. It was a larger house than the couple needed, indicated by the annual rent of £58 10s. As Crippen's salary, when he earned one, was £3 a week, it seemed strange that they should choose such a house, that Mrs. Crippen could afford to buy fox furs and jewellery and they could still put some money away. At the end of January 1910 Crippen was a few pounds overdrawn at the bank, but there was £600 on deposit, more than half of this sum was in his wife's name. As a guide to these monetary sums, whisky was 3s 6d a bottle and furs could cost £34.

Mrs. Crippen, under her assumed name of Belle Elmore, continued with her career as a music hall entertainer.

Mrs. Crippen attained some success in provincial halls, but she became well known and popular in certain theatrical circles. For two years before her death, she was Honorary Treasurer of the Music Hall Ladies Guild, which hired a room in Albion House. She was described as vivacious and pleasant, fond of dress and display, with a New York accent and dark hair which she dyed auburn. A Roman Catholic, she converted her husband to that faith.

In contrast to his wife, Crippen was a small man. He appeared to be mildness itself, an almost insignificant figure, dapper in dress, with a high, bald forehead, a heavy, sandy moustache, and rather prominent eyes behind gold-rimmed spectacles. Witnesses at his forthcoming trial described him as kindly, gentle and well mannered.

The Murder

The crisis, which ended with Crippen's execution, came in December 1909. His wife was tired of him, and she knew that Ethel le Neve had been his mistress. She threatened to leave Crippen, which would have been excellent news for him, but she was also planning to take their joint savings with her. On 15 December 1909, Mrs. Crippen gave notice of withdrawal to their bank. A month later, in January 1910, Crippen ordered five grains of hyoscin hydrobromide at Lewis and Burrow's shop in New Oxford Street. It was such a large order; they had to place a special order with the wholesalers. Crippen collected the order on 19 January 1910.

On the evening of 31 January 1910, there were two guests to dinner at 39 Hilldrop Crescent: a retired music-hall performer called Mr. Matinetti and his wife. After dinner, the Martinetti's and Crippen's played several games of whist. At 1.30am the following morning the Martinetti's left.

The next day, 1 February 1910, Crippen pawned a diamond ring and some earrings for £80, and that night Ethel le Neve slept at 39 Hilldrop Crescent. On 3 February 1910, two letters signed "Belle Elmore" and dated 2 February 1910, were received by the Secretary of the Music Hall Ladies Guild. Mrs. Crippen had resigned from her position as Honorary Treasurer, as she had been summoned to the USA, as one of her relatives had been taken seriously ill. The letters were not in Mrs. Crippen's handwriting. Mrs. Martinetti called on Crippen later that day, and rebuked him for not telling her directly about her friend's sudden departure. Crippen told her that they had been busy packing. "Packing and crying" replied Mrs. Martinetti, Crippen relied that they had got over that.

Crippen then pawned more rings and a broach for £115. On 20 February 1910, Crippen took Ethel le Neve to the ball of the Music Hall Ladies Benevolent Fund. It was noticed that le Neve was clearly wearing a broach, which was known to belong to Mrs. Crippen. On 12 March 1910, Ethel le Neve moved permanently into 39 Hilldrop Crescent. Shortly after this event, Crippen have his landlord's 3 months notice of his intention to vacate the house. Just before Easter 1910, Crippen told Mrs. Martinetti that Mrs. Crippen had been taken seriously ill in the USA, and that she was not expected to live. If she died, Crippen told Mrs. Matinetti that he would take a week's holiday in France.

On 24 March 1910, the day before Good Friday 1910, a telegram arrived for Mrs. Martinetti: "Belle died yesterday at 6pm". It had been sent from London's Victoria Rail Station, before Crippen and le Neve set off for Dieppe.

During his absence in France, Mrs. Crippen's friends had a great deal of discussions about their friends sudden trip to the USA, and her death. When he returned, Crippen made several attempts to prevent the sending of tokens of remembrance. Crippen stated that she had died in Los Angles, her ashes were returning to England and that gifts sent to the USA would arrive too late.

Everything was neatly explained, and the Crippen went around his normal business. Ethel le Neve was seen wearing more of Mrs. Crippen's furs and jewellery, which was regarded as being in poor taste.

A friend of the late Mrs. Crippen, a Mr. Nash, made a short visit to the USA where he made some unsuccessful enquires about Mrs. Crippen. When he returned to London, he went and spoke to Crippen. Dissatisfied with his answers, he went to Scotland Yard and told them his story.

A week after Mr. Nash's visit to Scotland Yard, Chief Inspector Dew called upon Mr. Crippen at his work place located in Albion House. He admitted that he had been lying about his wife's death. He believed that she was still alive, and she had gone to Chicago so she could be with her friend of her early music-hall days, Bruce Miller. His lies were to shield her and himself from any scandal that would result from her elopement. Dew then obtained a search warrant and visited Hilldrop Crescent, accompanied by Mr. Crippen. He found nothing and was beginning to believe Crippen's explanation regarding his wife disappearance.

Crippen & le Neve flee

For some reason, Crippen panicked and left for Antwerp, accompanied by le Neve who was disguised as a boy. When Dew returned to the house, just to check a couple of dates with Crippen, he found the house empty. He then raised the alarm.

While Crippen and le Neve's description was being widely circulated, Dew returned to Hilldrop Crescent and thoroughly searched thehouse. While in the coal cellar, Dew probed the brick floor and found the remains of Mrs. Crippen buried in lime

.

.

Ethel le Neve

During their voyage from Antwerp to Canada, Ethel le Neve disguised herself as a boy. The Montrose's Captain became suspicious of the couple's affectionate behaviour, and radioed his concerns back to London. Chief Inspector Drew boarded a faster ship, the SS Laurentic, and arrested the pair on 31 July 1910.

This was Spilsbury's first murder case and the one that established the reputation of his name. In his notes he recounts the discovery in the cellar: Human remains found 13 July . Medical organs of chest and abdomen removed in one mass. Four large pieces of skin and muscle, one from lower abdomen with old operation scar 4 inches long - broader at lower end. Impossible to identify sex. Hyoscine found 2.7 grains. Hair in Hinde's curler - roots present. Hair 6 inches long. Man's pyjama jacket label reads Jones Bros., Holloway, and odd pair of pyjama trousers.

There was no head, all the limbs were missing and no bones, except for what appeared to be part of a human thigh. One of the pieces of skin that was recovered had a scar, made as a result of an operation. The organs were analysed by Drs. Wilcox and Luff. The skin was analysed by Drs. Pepper assisted by Spilsbury.

The remains of Mrs. Crippen were eventually reburied in Finchley Cemetery, a week before the start of her husband trial.

It was decided that Crippen and le Neve would be tried separately.

The Trial

On 18 October 1910, Crippen's trial opened before Lord Chief Justice Lord Alverstone, in the No. 1 Court of London's Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey). The trial lasted five days. The prosecution's evidence was the purchase of the poison by Crippen, and that no one had seen Mrs. Crippen since the Martinetti's left the whist game early on the morning of 1 February 1910.

Crippen was defended by A.A. Tobin, KC (later a judge). Tobin was assisted by Mr Huntly Jenkins and Mr. Roome.

Prosecution witnesses on the 1st day included Mrs. Martinetti, other acquaintances of the Crippens, some of Mr. Crippen's business associates. Bruce Miller and Mrs. Crippen's sister travelled from the USA to provide evidence.

At the start of the 2nd day, Chief Inspector Dew gave evidence, including the reading of a long statement provided by Crippen. In the afternoon, Dr. Pepper took the stand. He stated that the mark on the piece of skin (produced in the court) was caused by an abdominal operation. Someone skilled in dissection, he stated, carried out the dismemberment of the body. The remains were those of an adult, young or middle-aged, but there was no certain anatomical indication of body's sex. When the remains had been examined, they had been buried for around 4 to 8 months. The burial had taken place soon after death had occurred. When asked by the prosecution whether the burial could have occurred before 21 September 1905 (when Crippen took up residence), Dr. Pepper relied "Oh, no, absolutely impossible." During cross-examination, Dr. Pepper was asked whether he had cut a piece of the skin sample across the area of the scar and handed it to Dr. Spilsbury. He confirmed that this was the case.

At the start of the 3rd day, 20 October 1910, Dr. Spilsbury was called to give evidence. He confirmed the analysis performed on the sample by Dr. Pepper, and that Dr. Pepper had provided him with a sample for microscopical analysis. Spilsbury stated that the provided sample was 1½ inches long, and almost ½ inch wide. It included a portion of the scar. At each end of this fragment he found glands, but there were none in the centre, proving that it was indeed a scar and not a skin fold. Spilsbury also stated that the presence and arrangement of certain muscles provided further proof that the specimen came from the lower abdomen.

The defence then asked Spilsbury how long he had been associated with Dr. Pepper, whether, before his own examination, he had heard that Mrs. Crippen had had an abdominal operation. Spilsbury replied that The fact that I have acted with Mr. Pepper has absolutely no influence upon the opinion that I have expressed here. The fact that I had read in the papers that there had been an operation on Belle Elmore had no effect at all upon the opinion I have expressed. I have no doubt that this is a scar."

The evidence presented by Wilcox and Luff took up the majority of this day. This concerned their analysis of the organs and other material found: a small portion of liver, one kidney, a pair of combinations, hair in a curler and three fragments of a pyjama jacket. The day finished with the opening of the defence, and the examination of Crippen by Mr. Huntly Jenkins.

The 4th day mainly consisted of Crippen's cross-examination by the prosecution. As the questioning continued, Crippen's replies became more vague and evasive. When asked when he purchased the pyjamas, Crippen replied that he had purchased them in either 1905 or 1906. A buyer for the firm Jones Brother of Holloway was able to prove that this pyjama material was not acquired by his firm until the end of 1908, and that three suits of pyjamas, made from this material, were delivered to 39 Hilldrop Crescent in January 1909. As the prosecution stated in their summing up, who alone during the next 12 months could have buried the jacket in that house? And "Who was missing who could be buried in it?"

After the trial

The jury took 27 minutes to find Crippen guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Ethel le Neve was tried 4 days later and found not guilty as an accessory after the fact.

On 23 November 1910, Crippen was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London. Before his execution, Crippen requested that a photograph of Ethel le Neve be buried with him.

Ethel le Neve sailed for New York, under the name of Miss Allen, on the morning of Crippen's execution. After reaching her final destination of Toronto, she started calling herself Ethel Harvey. Sometime during the period 1914-18, she returned to London and married a clerk called Stanley Smith. The couple settled down in Croydon and had several children, eventually becoming grandparents. Ethel died in hospital in 1967, aged 84.

The once "most famous house in London" (as some newspapers called 39 Hilldrop Crescent at the time) was destroyed, together with the surrounding houses, by German air raids in World War Two.John Reginald Halliday Christie

FROM : stephen-stratford.co.uk

Introduction

John Reginald Halliday Christie was a 54 year old serial murderer and sexual psychopath who murdered at least 6 women. He also gave evidence at the trial of Timothy Evans, who was executed (later posthumously pardoned) for crimes almost certainly committed by Christie (who had served in the Army during World War One and been a Special Police Constable during the Second World War).

The Case Details

In 1949 Christie lived at 10 Rillington Place, a grimy house in London's Notting Hill Gate. On the top floor of this building lived Timothy Evans, aged 24, a semi-literate van driver, with his wife and infant daughter.

On 30 November 1949 Evans walked into a police station in Wales and reported that he had found his wife dead in their London home, and had put her body down a drain. Later the bodies of his wife and child were found in the backyard; they had been strangled. Evans made a statement in which he confessed to the killings, but later he accused Christie. Christie, a witness at Evans trial at the Old Bailey in 1950, denied any responsibility. Evans was sentenced to death for the murder of his child, and was hanged on 9 March 1950 at Pentonville Prison.

On 24 March 1953 a West Indian tenant of 10 Rillington Place found a papered-over cupboard in Christie's former flat; it contained the bodies of three women. A fourth was found under the floorboards of another room, and the remains of two more in the garden. Christie admitted to murdering four women, on of them his wife, at 10 Rillington Place. The others, all in their twenties, were prostitutes. He later admitted to murdering the other two women in 1943 and 1944. He was then a special constable in the War Reserve Police.

Outwardly a respectable but unpopular man, Christie had served prison sentences for theft, and he was known as a habitual liar. In his teens he was known as "Reggie no dick" and "Can't do it Christie" on account of his sexual inadequacy.

Christie's motives were sexual; he admitted strangling one of his victims during intercourse. He related how he had invited women to the house and having got them partly drunk, sat them in a deck-chair, where he rendered them unconscious with domestic coalgas. He then strangled and raped them.

10 Rillington Place

Christie trial at the Old Bailey for his wife's murder began on 22 June 1953. The Judge was Mr Justice Finnemore, the Prosecution was led by the Attorney General Sir Lionel Heald and Christie was represented by Mr Curtis-Bennett. His defence plea was based on insanity. Three days' later the trial finished with Christie being found guilty of his wife's murder and sentenced to death.

Christie was hanged, on the same gallows as Evans had been 3 years earlier, at Pentonville Prison on 15 July 1953.

Among the various revelations at Christie's trial was his admission that he had also killed Mrs. Evans, although he denied having killed the baby.

The Home Secretary, Mr David Maxwell-Fyfe, initiated a private enquiry led by a senior barrister, Mr John Scott Henderson. The Henderson enquiry concluded that Evans had killed both his wife and daughter. This report was published on 13 July 1953, two days before Christie's execution. This report was controversial and appeared, to some people, as a white-washing exercise intended to protect the police's handling of the Evans case.

On 10 February 1965, Chuter Ede (the Home Secretary at the time of Evan's execution) said that the Evans' case showed how a mistake was possible and that one had been made.

Another inquiry, which was headed by Mr Justice Brabin, took place during the winter of 1965-1966. The Brabin Inquiry report was published, and found that Evans' had probably killed his wife and that he had not killed his daughter. As Evans had been convicted of his daughter Geraldine's murder, and not the murder of his wife, Evans was granted a posthumous pardon in 1966.

Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters

Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters

FROM : richard.clark.co.uk

Edith Thompson was a quite attractive 28 year old who was married to shipping clerk 32 year old Percy Thompson. They had no children and enjoyed a reasonable lifestyle, as Edith had a good job as the manageress of a milliners in London.

However, Edith was also having an affair with 20 year old Frederick Bywaters who was a ship's steward. Their relationship had started in June 1921 when he accompanied the Thompsons on holiday to the Isle of Wight. He moved in as lodger waiting for his next job on board ship but had been chucked out by Percy for getting too friendly with Edith. He witnessed a violent row between Edith and Percy and later comforted her. His ship was to sail on the 9th of September 1921, and he saw Edith secretly from time to time until ultimately booking into a hotel with her under false names.

He was a decisive (impulsive) young man who, at least according to him, decided on his own to stab Percy Thompson whom he felt was making Edith's life miserablehe felt was making Edith's life miserable.

.

Frederick Bywaters , Edith Thompson , Percy Thompson.

On October 4th, 1922, Bywaters lay in wait until just after midnight for Edith and Percy who were returning home to Ilford (in Essex) after a night out at a theatre in London and then stabbed Percy several times. Edith was said to have shouted "Oh don't!" "Oh don't! " Bywaters escaped and Percy died at the scene. Edith was hysterical but was questioned by police when she calmed down alleging that a strange man had stabbed Percy.

The Thompson's lodger, Fanny Lester, advised the police about Bywaters having also lodged with them, and they also learned that he worked for P & O, the shipping line.

The police discovered the letters that Edith had written to him and soon arrested him and charged him with the murder.

Edith was also arrested soon afterwards and charged with murder or alternatively with being an accessory to murder. She did not know that Bywaters had been arrested but saw him in the police station later and said "Oh God why did he do it", continuing "I didn't want him to do it".

Bywaters insisted that he had acted alone in the crime and gave his account as follows :

"I waited for Mrs. Thompson and her husband. I pushed her to one side, also pushing him into the street. We struggled. I took my knife from my pocket and we fought and he got the worst of it"

"The reason I fought with Thompson was because he never acted like a man to his wife. He always seemed several degrees lower than a snake. I loved her and I could not go on seeing her leading that life. I did not intend to kill him. I only meant to injure him. I gave him the opportunity of standing up to me like a man but he wouldn't". Bywaters stuck to this story during the trial which opened at the Old Bailey on December 6th, 1922 before Mr. Justice Shearman.

Edith had written no less than 62 intimate letters to Bywaters and stupidly they had kept them. In these, she referred to Bywaters as "Darlingest and Darlint". Some of them described how she had tried to murder Percy on several occasions. In one referring, apparently an attempt to poison him, she wrote, "You said it was enough for an elephant." "Perhaps it was. But you don't allow for the taste making it possible for only a small quantity to be taken." She had also tried broken glass, and told Bywaters that she had made 3 attempts but that Percy had discovered some in his food so she had had to stop.

Edith had sent Bywaters press cuttings describing murders by poisoning and had told Bywaters that she had aborted herself after becoming pregnant by him.

At the trial, Bywaters refused to incriminate Edith and when cross examined told the prosecution that he did not believe that Edith had actually attempted to poison Percy but had rather a vivid imagination and a passion for sensational novels that extended to her imagining herself as one of the characters.

Edith had been advised against going into the witness box by her lawyer but decided to do so and promptly incriminated herself by being asked what she had meant when she had written to Bywaters asking him to send her "something to give her husband." She said she had "no idea." Very unconvincing!

The judge in his summing up described Edith's letters as "full of the outpourings of a silly but at the same time, a wicked affection." The summing up was fair in law but the judge made much of the adultery.

Mr. Justice Shearman was obviously a very Victorian gentleman with high moral principles.

He also instructed the jury, however, "You will not convict her unless you are satisfied that she and he agreed that this man should be murdered when he could be, and she knew that he was going to do it, and directed him to do it, and by arrangement between them he was doing it."

The jury were not convinced by the defence case and took just over two hours to find them both guilty of murder on the 11th December. Even after the verdict was read out, Bywaters continued to defend Edith loudly. However, the judge had to pass the death sentence on both of them as required by law.

At the trial, Bywaters refused to incriminate Edith and when cross examined told the prosecution that he did not believe that Edith had actually attempted to poison Percy but had rather a vivid imagination and a passion for sensational novels that extended to her imagining herself as one of the characters.

Edith had been advised against going into the witness box by her lawyer but decided to do so and promptly incriminated herself by being asked what she had meant when she had written to Bywaters asking him to send her "something to give her husband." She said she had "no idea." Very unconvincing!

The judge in his summing up described Edith's letters as "full of the outpourings of a silly but at the same time, a wicked affection." The summing up was fair in law but the judge made much of the adultery.

Mr. Justice Shearman was obviously a very Victorian gentleman with high moral principles.

He also instructed the jury, however, "You will not convict her unless you are satisfied that she and he agreed that this man should be murdered when he could be, and she knew that he was going to do it, and directed him to do it, and by arrangement between them he was doing it."

The jury were not convinced by the defence case and took just over two hours to find them both guilty of murder on the 11th December. Even after the verdict was read out, Bywaters continued to defend Edith loudly. However, the judge had to pass the death sentence on both of them as required by law.

Edith was taken back to Holloway and Bywaters to Pentonville, prisons half a mile apart (in London) and placed in the condemned cells.

Both lodged appeals but these were dismissed.

She was an adulteress, an abortionist and possibly a woman who incited a murder or worse still had tried to poison her husband. At least this is how she was judged against the morals of the time. That is until she was sentenced to death. The public and the media that had been so against her now did a complete U-turn and campaigned for a reprieve. There was a large petition, with nearly a million signatures on it, to spare her. However this, even together with Bywaters repeated confession that he and he alone killed Thompson, failed to persuade the Home Secretary to reprieve her.

Both lodged appeals but these were dismissed.

She was an adulteress, an abortionist and possibly a woman who incited a murder or worse still had tried to poison her husband. At least this is how she was judged against the morals of the time. That is until she was sentenced to death. The public and the media that had been so against her now did a complete U-turn and campaigned for a reprieve. There was a large petition, with nearly a million signatures on it, to spare her. However this, even together with Bywaters repeated confession that he and he alone killed Thompson, failed to persuade the Home Secretary to reprieve her.

So at 9.00 a.m. on January 9th, 1923, both were executed in their respective prisons.

Bywaters met his end bravely at the hands of William Willis, still protesting Edith's innocence whilst she was in a state of total collapse. She had major mood swings even up to the morning of execution as she expected to be reprieved all along.

A few minutes before they entered the condemned cell, the execution party heard a ghastly moan come from Edith's cell. When John Ellis, the hangman, went in she was semi-conscious as he strapped her wrists. According to his biography, she looked dead already.

She was carried the short distance from the condemned cell to the gallows by two warders and the two assistants (Robert Baxter and Seth Mills) and held on the trap whilst Ellis completed the preparations.

Depending on whose version of events you read/believe, there was a considerable amount of blood dripping from her after the hanging. Some, including Bernard Spillsbury the famous pathologist who carried out the autopsy on her, claim it was caused by her being pregnant and miscarrying whilst others claim it was due to inversion of the uterus, and the authorities claim that nothing untoward happened at all. (They would, wouldn’t they!). Edith had been in custody for over 3 months before the execution so would have probably known she was pregnant. Under English law, the execution would have been staid until after she had given birth. In practice, she would have almost certainly been reprieved. She had everything to gain from claiming to be pregnant so it is surprising that she didn't if she had indeed missed two or three periods. However, she had aborted herself earlier and this may have damaged her uterus which combined with the force of the drop caused it to invert. The bleeding may equally have been the start of a heavy period. Research done in Germany before and during World War 2 on a large number of condemned women showed that menstruation was often interrupted by the stress of being tried and sentenced to death but could be brought on by the shock of being informed of the actual date of the execution, which in Edith's case was likely to have been only one or two days before she was hanged. Whatever the truth, this hanging seemed to have a profound effect on all those present.

Several of the prison officers took early retirement. John Ellis retired in 1923 and committed suicide in 1931.

Her body was buried "within the precincts of the prison in which she was last confined" in accordance with her sentence but was reburied at the massive Brookwood Cemetery in Brookwood, Surrey. in 1970, when Holloway Prison was being rebuilt.

Bywaters met his end bravely at the hands of William Willis, still protesting Edith's innocence whilst she was in a state of total collapse. She had major mood swings even up to the morning of execution as she expected to be reprieved all along.

A few minutes before they entered the condemned cell, the execution party heard a ghastly moan come from Edith's cell. When John Ellis, the hangman, went in she was semi-conscious as he strapped her wrists. According to his biography, she looked dead already.

She was carried the short distance from the condemned cell to the gallows by two warders and the two assistants (Robert Baxter and Seth Mills) and held on the trap whilst Ellis completed the preparations.

Depending on whose version of events you read/believe, there was a considerable amount of blood dripping from her after the hanging. Some, including Bernard Spillsbury the famous pathologist who carried out the autopsy on her, claim it was caused by her being pregnant and miscarrying whilst others claim it was due to inversion of the uterus, and the authorities claim that nothing untoward happened at all. (They would, wouldn’t they!). Edith had been in custody for over 3 months before the execution so would have probably known she was pregnant. Under English law, the execution would have been staid until after she had given birth. In practice, she would have almost certainly been reprieved. She had everything to gain from claiming to be pregnant so it is surprising that she didn't if she had indeed missed two or three periods. However, she had aborted herself earlier and this may have damaged her uterus which combined with the force of the drop caused it to invert. The bleeding may equally have been the start of a heavy period. Research done in Germany before and during World War 2 on a large number of condemned women showed that menstruation was often interrupted by the stress of being tried and sentenced to death but could be brought on by the shock of being informed of the actual date of the execution, which in Edith's case was likely to have been only one or two days before she was hanged. Whatever the truth, this hanging seemed to have a profound effect on all those present.

Several of the prison officers took early retirement. John Ellis retired in 1923 and committed suicide in 1931.

Her body was buried "within the precincts of the prison in which she was last confined" in accordance with her sentence but was reburied at the massive Brookwood Cemetery in Brookwood, Surrey. in 1970, when Holloway Prison was being rebuilt.

Comment.

Although there is no evidence suggesting that Edith had any physical part in the murder and I personally tend to believe that she did not actually intend Bywaters to kill Percy, there is the problem of "common purpose."

In law if two people want a third person dead and conspire together to murder that person, it does not matter which one of them struck the fatal blow, both are equally guilty.

The law has always liked written evidence because it is much safer and stronger than hearsay evidence or the confused statements of witnesses. In this case they had a veritable pile of it, mostly incriminating. Letters that talked about poisoning Percy and letters asking Bywaters to "do something" etc.

The jury accepted the prosecution case that all this added up to common purpose to murder Percy, after a short 2-1/4 hour discussion.

So was she evil or just a silly, over romantic woman who gave no thought to the consequences of her irresponsible letters? My personal view having studied the case is that she was the latter.

It should be said that divorce was much harder in those days. If Percy refused to divorce her, which he had, her only alternatives were to run away with Bywaters or kill Percy.

As in all capital cases, the Home Secretary had the power of reprieve and many people were shocked that he did not exercise it in this case. I feel that he should have given her the benefit of the doubt. Her crime was hardly in the same class as 4 of the other 7 women who had been hanged since the beginning of the century – they had been Baby Farmers!

George Joseph Smith....the "Brides in the Bath" case

George Joseph Smith

FROM: historybyhteyard.co.uk

It was a report in The News of the World about the tragic inquest of Margaret Lloyd, a bride who had drowned in her bath in Highgate a week before Christmas 1914 which prompted a Mr Charles Burnham and a Mrs Crossley to go to the police, and which brought Divisional Detective Inspector Neil of the Metropolitan Police to investigate a complicated case of bigamy and murder.

Mr Burnham was a Buckingham fruit grower whose 25-year old daughter Alice had married George Smith in Portsmouth in November 1913, despite parental objections. The couple went on a holiday to Blackpool where Mrs Crossley had been their landlady. Alice had also drowned in her bath just on 12th December 1913, not long after her wedding in October of that year.

When John Lloyd attended his solicitor's office to receive the money due to him as the result of the death of Margaret Lloyd (nee Lofty) the police were waiting for him, and he later admitted that he was the same man George Smith who had married Alice Burnham.

The year before Alice Burnham's death in Blackpool, Bessie Munday had died on 13th July 1912 whilst taking a bath in Herne Bay where she was staying with her husband, Henry Williams, whom she had married in Weymouth in August 1910. "Henry Williams" transpired to be none other than George Smith.

Enquiries showed that Smith had conducted seven bigamous marriages between 1908 and 1914.

At the age of 26, in January 1898, using the name of George Love, Smith had married, legally and for the first time, 18-year old Caroline Thornhill in Leicester. They moved to London, and she worked as a maid for a number of employers, stealing from them under her husband's tuition. Caroline Love was arrested in Worthing, trying to pawn some silver spoons, and she was sent to prison for 12 months. On her release she incriminated her husband, who was then jailed for two years in January 1901. On his release , Mrs Love fled to Canada.

In June 1908 Smith met a widow from Worthing, Florence Wilson, and married her three weeks later. By 3rd July he had left her after taking £30 she had withdrawn from her savings account, and selling all her belongings.

By 30th July 1908 he had married Edith Pegler in Bristol who had replied to his advertisement for a house keeper. Then, in October 1909 he married Miss Sarah Freeman, using the name of George Rose. He also married Alice Reid in September 1914, using the name of Charles Oliver James.

Smith apparently had a masterful, hypnotic way with some women, a trait which was only exceeded by his ruthlessness in acquiring their money. ruthlessness in acquiring their money.

SMITH in the dock at the Old Bailey. The photo was taken secretly.

When he appeared at the Old Bailey, charged with murdering Alice Burnham, Bessie Munday and Margaret Lloyd, Detective Inspector Neil demonstrated to the jury the method of drowning his victims by raising their knees whilst they were in the bath. His assistant, a nurse in a bathing costume, herself required artificial respiration after the court room demonstration, and Smith was duly convicted.

Smith's trial took place during the dark days of the First World War, and the Judge, Mr Justice Scrutton, remarked upon the irony that "..while this wholesale destruction of human life is going on, for some days all the apparatus of justice in England has been considering whether one man should die..." The jury returned their Guilty verdict in 22 minutes, and Smith was executed on Friday 13th August at Maidstone prison.

Caroline Thornhill, whom Smith had married legally, was now a widow, and she married a Canadian soldier the day after Smith's execution.

William Joyce : LORD HAW HAW

William Joyce : LORD HAW HAW

FROM stephen-stratford.co.uk

Introduction

The case of William Joyce must be one of the most famous treason trials in British legal history. Due to the legal issues involved, the case went to the House of Lords (the highest English court). Joyce did not deny that he committed the acts alleged, he denied that he had a duty of allegiance and so could not be guilty of treason.Early Life

William Joyce was born on 24 April 1906 in Brooklyn, New York. He was the son of Michael and Gertrude Emily Joyce. Michael Joyce, originally came from Ireland, and became a naturalised American citizen on 25 October 1894.Three years after William's birth, the Joyce family returned to Ireland. They moved around several Irish counties during the First World War years. For immigration and registration reasons, Michael Joyce obtained a copy of his son's birth certificate which was issued in New York on 2 November 1917.

In 1922 the Joyce family moved to England. Following William passing his London Matriculation examination in 1922, he applied for enrolment in the University of London Officer's Training Corps (OTC). This application was accompanied by a letter from Michael Joyce stating that "We are all British, not American citizens".

In 1922 William Joyce started studying Science at Battersea Polytechnic. A year later, Joyce left his science course and stared on a English Language, Literature with history course at Birbeck college. He graduated in 1927.

Following his coming-of-age, William Joyce married Hazel Kathleen Barr at Chelsea Register Office on 30 April 1927.

The Thirties

The period 1933-37 was a hectic time in Joyce's life. During this time, Joyce studied a one year post-graduate course in Philology, and during 1931-3 a psychology course at King's College London. Also during this time period he was a member of Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascist's (BUF) movement. This movement had several clashes with the police. This resulted in Oswald Mosley, William Joyce and two others being tried, and acquitted, before Mr. Justice Branson of taking part in a riotous assembly at Worthing. On 4 July 1934, William Joyce applied and obtained his British Passport.Following the dissolving of his first marriage in 1936, William Joyce married Margaret Cairns White at Kensington Register Office (London) on 13 February 1937; the marriage witnesses being Mrs. Hastings Bonora and John A. Macnab. After becoming disgruntled with Mosley's B.U.F organisation in 1937, Joyce founded his National Socialist League and Margaret Joyce became the League's Assistant Treasurer. In 1938, he extended his British Passport by one year.

On 17 November 1938, charges of assault against William Joyce were dismissed by Mr. Paul Bennett at West London Police Court. William Joyce was again in court on 22 May 1939, when charges against him under the Public Order Act were dismissed by Mr. Marshall at Westminster Police Court.

Joyce in Germany

In July 1939 William Joyce sent a letter to a suspected German agent in the UK. He revealed in the letter that he was planning to travel to Germany. At this time, MI5 had produced a report that recommended that when war with Germany was declared, William Joyce should be detained.In August 1939, just before the outbreak of war, Joyce renewed his British Passport for another year and dissolved his National Socialist League. On 1 September 1939, two days before war was declared, Special Branch detectives went to arrest Joyce at his Earl's Court home. However, they found that William Joyce and his wife had left for Germany on 26 August. Joyce's sister claimed that a MI5 agent had tipped off Joyce that he was about to be arrested.

During Late 1939 and early 1940, while his British Passport was still valid, William Joyce made several radio broadcasts in English. Because William Joyce held a British Passport he had a duty of allegiance to the British crown. By broadcasting for the Germans, Joyce broke that allegiance and consequently committed high treason (See my article on the treason and treachery acts for a greater explanation of treason).

Shortly after his passport expired, Joyce fell out of favour with the Germans. He continued to make radio broadcasts to the U.K. Joyce's nickname of "Lord Haw Haw" was given him by a correspondent in a Daily Express article:

"A gent I'd like to meet is moaning periodically from Zeesen [the site in Germany of the English transmitter]. He speaks English of the haw-haw, damit-get-out-of-my-way variety, and his strong suit is gentlemanly indignation."

In was in fact Baillie-Stewart who made the September 1939 radio broadcast which was heard by Jonah Barrington (a pen-name used by a Daily Express correspondent). After hearing this broadcast, Barrington wrote about a gentleman speaking with an English accent of the haw-haw type, get-out-of-my-way type. On 18 September 1939, Barrington wrote for the first time about Lord Haw-Haw. These comments were aimed at Baillie-Stewart 'the Sandhurst-educated officer and gentleman' (who made the broadcast heard by Barrington) and not the nasal-accented William Joyce.

It should be remembered that these broadcasts were made at a time of very heavy German air raids. While people regarded the broadcasts as something of a joke, Joyce was regarded as a traitor who would hopefully get what he deserved.

William Joyce made radio broadcasts throughout the war, although during his last broadcast he was heavily drunk.

He was arrested by British Troops near Flensburg on the Danish-German border. They came across what appear to be a German civilian, whose voice sounded familiar. It eventually dawned who he was. When they challenged Joyce, he put his hand into a pocket. Thinking that he was going for a pistol, the British troops shot Joyce in the leg.

Joyce's Arrest

After recovering in Lueneberg Military Hospital, William Joyce arrived as a prisoner in the U.K on 16 June 1945. The day before Joyce's arrival, the Treason Act 1945 had been granted Royal Assent by King George VI. William Joyce was charged with three counts of high treason.Due to the need for evidence, concerning the important question of Joyce's nationality, from the U.S.A, the crown court case was put back to September.

The Trial

On 17 September in the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey, before Mr. Justice Tucker and a jury, William Joyce was charged with three counts of High Treason:1. William Joyce, on the 18 September 1939, and on numerous other days between 18 September 1939 and 29 May 1945 did aid and assist the enemies of the King by broadcasting to the King's subjects propaganda on behalf of the King's enemies.

2. William Joyce, on 26 September 1940, did aid and comfort the King's enemies by purporting to be naturalised as a German citizen.

3. William Joyce, on 18 September 1939 and on numerous other days between 18 September 1939 and 2 July 1940 did aid and assist the enemies of the King by broadcasting to the King's subjects propaganda on behalf of the King's enemies.

The trial lasted three days: 17,18 and 19 September 1945. The main arguments in the case concerned whether the defendant had a duty of allegiance to the King. If there was no duty of allegiance, then Joyce could not be found guilty of treason. William Joyce did not deny carrying out the alleged acts, he just denied that he owed any allegiance to the King.

The prosecution accepted that under counts 1 and 2 Joyce did not owe allegiance as he was an American citizen. However, they argued that as he held a British Passport and left the U.K on this passport he had the protection given to passport holders. As protection demands allegiance, Joyce broke this allegiance and committed treason. This point in law was accepted by Mr. Justice Tucker, who ruled that the prosecution's point in law was valid. The judged also directed the jury to find Joyce not guilty of counts 1 and 2.

Following the judge's ruling, the jury was left with the question of whether Joyce had made the broadcasts between the dates of 18 September 1939 and 2 July 1940 (the period when Joyce's British Passport was valid). They decided that Joyce had made the broadcasts, and they found him guilty of count 3.

As High Treason carried a mandatory capital sentence, the judge sentenced William Joyce to death by hanging.

Court of Appeal

On 27 September 1945, Joyce's lawyers gave notice of appeal. Due to high treason having only one possible sentence, they could only appeal the conviction not the sentence itself. His lawyers argued that the trial judge was wrong to accept the prosecution's legal arguments relating to the question of allegiance. They argued that the fact the King was unable to offer protection to Joyce in Germany, that Joyce was an American citizen and that Joyce never intended to ask for protection, meant that as no protection was asked for, no allegiance was owed in return.William Joyce's appeal was heard before the Lord Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Humphreys and Mr. Justice Lynskey, on 30 October 1945. On 1 November 1945, they announced that judgement was reserved. On 7 November 1945, it was announced that the appeal was dismissed. In effect, they supported the prosecution argument relating to the protection offered by the British Passport, and the consequent allegiance demanded.

House of Lords

Due to the important questions of law involved in the case, the Attorney-General granted his certificate on 16 November 1945, which allowed the case to be heard before the House of Lords; the highest British court.The appeal before the House of Lords on 10 to 13 December 1945, was heard by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Macmillan, Lord Wright, Lord Porter and Lord Simonds. This appeal was dismissed, with Lord Porter dissenting, on 18 December 1945. They also announced that they would give their reasons at a later date.

The Execution

At a few minutes past 9am on 3 January 1946, with a sizeable crowd outside the prison, William Joyce was hanged at Wandsworth Prison in London. After the post-mortem and inquest in the afternoon, William Joyce was buried in unconsecrated ground within the prison grounds (as with all executed prisoners).On 18 August 1976, William Joyce's remains were exhumed and returned for burial in Ireland.

Margaret Joyce

William Joyce's wife, Margaret, was arrested the same day as Joyce and returned to London's Holloway Prison.It was decided after the war that no further action would be taken against William Joyce's wife Margaret. Although she was born in Manchester, had apparently made no effort to renounce her British Citizenship after arriving with her husband in Germany and made German propaganda radio broadcasts to the UK, no proceedings were taken against her. In documents at the PRO, a MI5 officer admitted that the decision was in effect based on compassionate grounds; namely the trial and execution of her husband.

Margaret Joyce died in London during 1972.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)